1.2 Israel’s great narratives

“You shall love the alien as yourself,” (or “You know the heart of an alien”). These laws of Moses are found in the Book of Leviticus. “Locals” are reminded not to forget that they themselves were once strangers. Yet not everyone was friendly to foreigners back then either…

The narrative of being driven out of Paradise (Gen 3:23–24) and Cain’s going “east of Eden“ (Gen 4:16 ff.) shows that the biblical authors basically imagine human history and the development of culture and civilization as a migration event.

But biblical Israel also tells its own story – and Judaism follows it to this day – as one of multiple migrations. This applies above all to the stories of the mothers and fathers of Israel, the ‘arch-parents’, to their paths out of Mesopotamia to Canaan and their lives as ‘strangers’ in the Promised Land. From the beginning of the narrative we are aware of Israel’s self-awareness of having been chosen by God and called to follow its own path, under the blessing, that God gives with this special story to “all the families of the earth” (Gen 12:1–4).

In the context of this sending, the texts also contain the intention and religious duty to preserve their own identity in the foreign country by living among themselves, their relatives and families – as Judaism lived for millennia and as can be found in many migrant communities to this day.

At the same time, however, and on this basis, the arch-parent stories (Gen 12:50) mostly tell of peaceful conflict resolution; they describe cooperation and respectful border drawing towards others and underline also the mutual religious communication between the family of Abraham and the other inhabitants of the land. The latter recognize the special relation to God of the arch-parents (Gen 23:8; cf. 14:18), and the former learn that the fear of God is also there where they least expect it (Gen 20:14), and that they are called to pray for the good of the others (Gen 20:17).

The Exodus story, Israel‘s second great migration narrative, is more political and combative. It bears witness to God’s option for the oppressed slaves of the state of Egypt and shows how necessary it is for freedom to depend on law and precept. The Torah – i.e. all the law that is to apply in Israel – relates to this experience of liberation and journeying. It serves freedom and is the gift from the God of freedom (Ex 20:1).

Particularly in texts and stories dealing with the memory of the Exodus and the occupying of the land of Canaan we are struck by the sometimes openly hostile tones towards certain other peoples. These texts frequently mirror the brutal experiences of oppression and violence that Israel itself suffered under the different ancient empires.

Foreignness and law

Foreignness and lawIt is remarkable, however, that “the strangers” in the Torah certainly have their own rights. Apart from another word meaning an alien passing by, the Hebrew word for “foreign” (ger) means people who permanently live in a place but do not stem from there. They do not belong to one of the resident clans and therefore have no rights as full (male) citizens with their own property. The different legal traditions of the Torah lay down in detail the way aliens have to hold to the religious customs of Israel – e.g. to rest on the Sabbath – and under what conditions they are allowed to take part in Israel’s worship services.

Second, the greatest value is attached to how the members of Israel must behave towards the aliens. Here aliens are, so to speak, a yardstick of just social legislation (Ex 22:20-23:9). Because of their weak position – like that of Israeli widows and orphans – special protection against economic, social and legal attacks, and special welfare regulations apply to the guaranteeing social assistance of the kind received by needy Israelites (Deut 14:29).

As a reason and motivation for loving the alien like yourself (Lev 19:33) there is multiple emphasis that “you [i.e. Israel] were aliens in Egypt” (Ex 22:21). “You know the heart of an alien” (Ex 23:9).

The heart of biblical ethics regarding strangers therefore beats the rhythm of memory. Precisely when you are enjoying the wealth and gifts of your own country you should remember that you yourself were not always there and are not alone there now, either. The local people receive the commission to keep remembering their own life as aliens – even if they have been sedentary for generations.

Just like today, this was probably not the rule back then either. Otherwise there would not be such strict emphasis on protection (Ex 22:20), participation and the ideal of equal treatment of the aliens (Num 15:15f). The reality in biblical times was not idyllic for foreigners. Otherwise the biblical texts would not contain fantasies of the strict subjugation of aliens or even ideas about strictly excluding them from Israel (Neh 13). Here we sense a severe and anxious view of aliens. It reflects negative fears or experiences, inner tensions, the feeling of threat to their own identity and the wish to protect it. In the background is the culturally and politically troubled situation of the Jewish community under the pressure of ancient empires. There is a tangible concern that marrying ‘foreign’ women could lead to a falling away from God (Deut 7:23) and to the loss of Israel’s special identity.

Shifting borders

Yet this view does not remain without contradiction in Israel’s Hebrew Bible and our Old Testament. This is shown, for example, by the story about the two widows, Naomi and Ruth. Naomi, an Israelite, returns from the neighboring country of Moab with her Moabite daughter-in-law Ruth. During a famine she had been well received there and found wives for her sons.

Due to a certain view by Israel of the past and its identity, marrying the members of this people was clearly contrary to the will of God (cf. Ezra 9–10; Neh 13:23–27). In the case of the Moabites, the Torah (Deut 23:4) states that the Moabites had once refused Israel bread and water when they were on their way through the wilderness.

The story of Ruth reports the opposite and so undermines the basic assumption of exclusion as required by the relevant verse of the Torah. Ruth, the Moabite, looks after Naomi, the Israelite. Her solidarity sets in motion a whole flow of human goodness and overcomes borders. God acts (Ruth 2:10-12). They both – a ‘national’ and a foreigner – benefit from their gifts of mutual goodness.

Not only is Ruth, the foreigner, able to stay in Israel. The story likewise underlines that Naomi, the socially disadvantaged Israelite (Ruth 4:14-15), flourishes again and there is an increase of blessing and well-being in the whole of Israel.

The final note in the book of Ruth (Ruth 4: 17-22) takes this up. She, the migrant, is the great-grandmother of David, i.e. of the greatest and most glorious king of Israel. And the beginning of the New Testament continues this line of thinking by explicitly naming Ruth as an ancestral mother of Jesus (Mt 1:5).

Read more about David in the resources for Bible study provided online by the German Bible Society: David im Bibellexikon.

Read more about the Torah in the resources for Bible study provided online by the German Bible Society: Torah im Bibellexikon.

Da wies ihn Gott der Herr aus dem Garten Eden, dass er die Erde bebaute, von der er genommen war. Und er trieb den Menschen hinaus und ließ lagern vor dem Garten Eden die Cherubim mit dem flammenden, blitzenden Schwert, zu bewachen den Weg zu dem Baum des Lebens. (1. Mose 3,23–24)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

So ging Kain hinweg von dem Angesicht des Herrn und wohnte im Lande Nod, jenseits von Eden, gegen Osten. (1. Mose 4,16)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

1 Und der Herr sprach zu Abram: Geh aus deinem Vaterland und von deiner Verwandtschaft und aus deines Vaters Hause in ein Land, das ich dir zeigen will. 2 Und ich will dich zum großen Volk machen und will dich segnen und dir einen großen Namen machen, und du sollst ein Segen sein. 3 Ich will segnen, die dich segnen, und verfluchen, die dich verfluchen; und in dir sollen gesegnet werden alle Geschlechter auf Erden. 4 Da zog Abram aus, wie der Herr zu ihm gesagt hatte, und Lot zog mit ihm. Abram aber war fünfundsiebzig Jahre alt, als er aus Haran zog. (1. Mose 12,1–4)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Und er redete mit ihnen und sprach: Gefällt es euch, dass ich meine Tote hinaustrage und begrabe, so höret mich und bittet für mich Efron, den Sohn Zohars… (1. Mose 23,8)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Aber Melchisedek, der König von Salem, trug Brot und Wein heraus. Und er war ein Priester Gottes des Höchsten (1. Mose 14,18)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Abraham sprach: Ich dachte, gewiss ist keine Gottesfurcht an diesem Orte, und sie werden mich um meiner Frau willen umbringen. (1. Mose 20,11)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Abraham aber betete zu Gott. Da heilte Gott Abimelech und seine Frau und seine Mägde, dass sie wieder Kinder gebaren. (1. Mose 20,17)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Und Gott redete alle diese Worte (2. Mose 20,1)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Kapitel 22

20 Einen Fremdling sollst du nicht bedrücken und bedrängen; denn ihr seid auch Fremdlinge in Ägyptenland gewesen.

21 Ihr sollt Witwen und Waisen nicht bedrücken. 22 Wirst du sie bedrücken und werden sie zu mir schreien, so werde ich ihr Schreien erhören. 23 Dann wird mein Zorn entbrennen, dass ich euch mit dem Schwert töte und eure Frauen zu Witwen und eure Kinder zu Waisen werden. 24 Wenn du Geld verleihst an einen aus meinem Volk, an einen Armen neben dir, so sollst du an ihm nicht wie ein Wucherer handeln; ihr sollt keinerlei Zinsen von ihm nehmen. 25 Wenn du den Mantel deines Nächsten zum Pfande nimmst, sollst du ihn wiedergeben, ehe die Sonne untergeht, 26 denn sein Mantel ist seine einzige Decke auf der bloßen Haut; worin soll er sonst schlafen? Wird er aber zu mir schreien, so werde ich ihn erhören; denn ich bin gnädig.

27 Gott sollst du nicht lästern, und einem Obersten in deinem Volk sollst du nicht fluchen. 28 Den Ertrag deines Feldes und den Überfluss deines Weinberges sollst du nicht zurückhalten. Deinen ersten Sohn sollst du mir geben. 29 So sollst du auch tun mit deinem Stier und deinem Kleinvieh. Sieben Tage lass es bei seiner Mutter sein, am achten Tage sollst du es mir geben. 30 Ihr sollt mir heilige Leute sein; darum sollt ihr kein Fleisch essen, das auf dem Felde von Tieren zerrissen ist, sondern es vor die Hunde werfen.

Kapitel 23

1 Du sollst kein falsches Gerücht verbreiten; du sollst nicht einem Schuldigen Beistand leisten, indem du als Zeuge Gewalt deckst.2 Du sollst der Menge nicht auf dem Weg zum Bösen folgen und nicht so antworten vor Gericht, dass du der Menge nachgibst und vom Rechten abweichst. 3 Du sollst den Geringen nicht begünstigen in seiner Sache. 4 Wenn du dem Rind oder Esel deines Feindes begegnest, die sich verirrt haben, so sollst du sie ihm wieder zuführen. 5 Wenn du den Esel deines Widersachers unter seiner Last liegen siehst, so lass ihn ja nicht im Stich, sondern hilf mit ihm zusammen dem Tiere auf. 6 Du sollst das Recht deines Armen nicht beugen in seiner Sache. 7 Halte dich ferne von einer Sache, bei der Lüge im Spiel ist. Den Unschuldigen und den, der im Recht ist, sollst du nicht töten; denn ich lasse den Schuldigen nicht recht haben. 8 Du sollst dich nicht durch Geschenke bestechen lassen; denn Geschenke machen die Sehenden blind und verdrehen die Sache derer, die im Recht sind. 9 Einen Fremdling sollst du nicht bedrängen; denn ihr wisst um der Fremdlinge Herz, weil ihr auch Fremdlinge in Ägyptenland gewesen seid. (2. Mose 22,20–23,9)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Dann soll kommen der Levit, der weder Anteil noch Erbe mit dir hat, und der Fremdling und die Waise und die Witwe, die in deiner Stadt leben, und sollen essen und sich sättigen, auf dass dich der Herr, dein Gott, segne in allen Werken deiner Hand, die du tust. (5. Mose 14,29)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

33 Wenn ein Fremdling bei euch wohnt in eurem Lande, den sollt ihr nicht bedrücken. 34 Er soll bei euch wohnen wie ein Einheimischer unter euch, und du sollst ihn lieben wie dich selbst; denn ihr seid auch Fremdlinge gewesen in Ägyptenland. (3. Mose 19,33f)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Einen Fremdling sollst du nicht bedrücken und bedrängen; denn ihr seid auch Fremdlinge in Ägyptenland gewesen. (2. Mose 22,20)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Für die ganze Gemeinde gelte nur eine Satzung, für euch wie auch für die Fremdlinge. Eine ewige Satzung soll das sein für eure Nachkommen, dass vor dem Herrn der Fremdling sei wie ihr. Einerlei Ordnung, einerlei Recht soll gelten für euch und für den Fremdling, der bei euch wohnt. (4. Mose 15,15 f.)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Der Herr, dein Gott, wird sie vor dir dahingeben und wird eine große Verwirrung über sie bringen, bis sie vertilgt sind. (5. Mose 7,23)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

10 Da fiel sie auf ihr Angesicht und beugte sich nieder zur Erde und sprach zu ihm: Womit hab ich Gnade gefunden vor deinen Augen, dass du mir freundlich bist, die ich doch eine Fremde bin? 11 Boas antwortete und sprach zu ihr: Man hat mir alles angesagt, was du getan hast an deiner Schwiegermutter nach deines Mannes Tod; dass du verlassen hast deinen Vater und deine Mutter und dein Vaterland und zu einem Volk gezogen bist, das du vorher nicht kanntest. 12 Der Herr vergelte dir deine Tat, und dein Lohn möge vollkommen sein bei dem Herrn, dem Gott Israels, zu dem du gekommen bist, dass du unter seinen Flügeln Zuflucht hättest. (Ruth 2,10–12)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Da sprachen die Frauen zu Noomi: Gelobt sei der Herr, der dir heute den Löser nicht versagt hat! Sein Name werde gerühmt in Israel! 15 Der wird dich erquicken und dein Alter versorgen. Denn deine Schwiegertochter, die dich geliebt hat, hat ihn geboren, die dir mehr wert ist als sieben Söhne. (Ruth 4,14–15)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

17 Und ihre Nachbarinnen gaben ihm einen Namen und sprachen: Noomi ist ein Sohn geboren; und sie nannten ihn Obed. Der ist der Vater Isais, welcher Davids Vater ist. 18 Dies ist das Geschlecht des Perez: Perez zeugte Hezron; 19 Hezron zeugte Ram; Ram zeugte Amminadab; 20 Amminadab zeugte Nachschon; Nachschon zeugte Salmon; 21 Salmon zeugte Boas; Boas zeugte Obed; 22 Obed zeugte Isai; Isai zeugte David. (Ruth 4,17–22)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Salmon zeugte Boas mit der Rahab. Boas zeugte Obed mit der Rut. Obed zeugte Isai. (Matthäus 1,5)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Einen Fremdling sollst du nicht bedrängen; denn ihr wisst um der Fremdlinge Herz, weil ihr auch Fremdlinge in Ägyptenland gewesen seid. (2. Mose 23,9)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Die Ammoniter und Moabiter sollen nicht in die Gemeinde des Herrn kommen, auch nicht ihre Nachkommen bis ins zehnte Glied; sie sollen nie hineinkommen, … (5. Mose 23,4)

Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

1.3 Jesus Christus – on the move and a stranger

The New Testament also tells of being foreign or even homeless. Yet the first Christian communities “brought people from the Jewish tradition together with people of other ethnic, cultural, political and religious traditions”. What conclusions should churches and Christians draw today when they refer to Scripture?…

The people around Jesus and the early Christian communities lived with and from the Bible of Israel. They knew its symbolism of being on the move and trusted it. On this basis they interpreted their experiences with Jesus the Messiah.

The gospels describe the earthly Jesus as a person who is normally moving around. His path mirrors God’s coming closer (Mk 1:14). His journey and that of his disciples maps out Israel’s journey with God and takes it further (Mt 2). Jesus’ coming, staying and going to the Father are, particularly in the farewell addresses of John’s gospel (Jn 13-17), basic descriptions of the being of God’s Son and the power of faith.

Ethnic boundaries like those between Israel, the People of God, and the other peoples are known in the gospels and in some cases even emphasized (Mt 10:5). But, at the same time, Jesus also learns how to cross boundaries (Mt 15:21–28), to people’s great surprise. Not only they, but also Jesus learns along the way, as the gospels describe. And the risen Christ extends the learning community to embrace all nations (Mt 20:28)

The Acts of the Apostles tell of how it is God’s will, guided by God’s spirit, that faith in Christ also reaches non-Jews (Acts 10). At the same time it becomes recognizable that the new “Way” (Acts 9:2) was actually able to turn the believers into migrants (Acts 11:19–20). Like the well-planned missionary journeys, fleeing and persecution (Acts 18:1–3; cf. Rm 16:3–4) were also part of the story of the emergence and dissemination of early Christianity.

Even though crossing over from Asia to Europe, i.e. from today’s Turkey to the Greek mainland, was probably not so important culturally in antiquity as it is today, the book of Acts underlines this step (Acts 16:9–40). Interestingly, when the Apostles and the message of Christ arrive on the European mainland in the city of Philippi (Acts 16:11–15.40) they first find hospitality and then faith in the person of a cloth dealer called Lydia, who – as her name suggests – probably came from Asia, i.e. from the western Turkish region of Lydia. This not only shows the extent to which migration determined everyday and working life in antiquity. The dawn of “Christian Europe” was hence marked by the hospitality of a migrant, and, according to the story in Acts, Europe’s first Christian was from Asia Minor.

The young congregations brought people from the Jewish tradition together with people of other ethnic, cultural, political and religious traditions. Engaging with different traditions and thinking was part of daily life. That also led to fierce conflicts (Rm 14; Gal 2:11–14; 5:1–6), e.g. regarding the food laws or circumcision, and to various compromises (1 Cor 8; Acts 15). Paul’s teaching on justification by faith is also rooted in this struggle for unity in diversity. Baptism creates unity and equality between different persons (Gal 3:28). Those who belong to Christ and belong in him are not decided by the restrictions of ritual purity and social exclusion as laid down by the Torah for Jews. The dividing wall of being strangers to God has been broken down. Christ and his death also make non-Jews into members of the household of God (Eph 2:12–19).

Christ in a foreign country

“I was a stranger and you welcomed me/did not welcome me” (Mt 25:35.38.43). That is what Jesus says of himself in his parables – he the son of man and king who has come to judge the world. The message of the parables is plain and subtle at the same time. It is plain because – as with the behavior towards the hungry and thirsty, naked, sick and prisoners – the kingly judge of the world will, at the end of time, also take personally the action or non-action towards strangers, “the least of these who are members of my family”. The foreigners are here grouped with other socially disadvantaged persons, who then cannot be played off against each other. The parable speaks neither of preferring nor of disadvantaging strangers over other needy persons.

According to the Old Testament, whoever oppresses dispossessed persons also despises the creator (Prov 14:31), as they are made in the image of God. Likewise the judge of the world in the parable of Jesus also relates the (dis)respect for the least of the “members of my family” to himself. It is this view that places each low and needy person in a new reality by relating him or her to Christ.

The message of the parable is subtle, as well, since it plays with the aspect of surprise. The righteous people ask, “When did we see you as a stranger and did not welcome you?”

Strangers – whether sick, hungry or prisoners – should therefore not be co-opted right away for Christ, or even as Christ, but it is right always to expect to be surprised by Christ in the stranger.

Being Christian as being a stranger – the itinerant people of God

The New Testament letters, in particular, constantly stress that being a stranger, or even having no home, is part of the life of faith. The young congregations recognize themselves in the migration and stories of being strangers of the Hebrew Bible, in the concepts and the images of being on the move and of migration. For example, the author of 1 Peter uses the word “exiles” to address the congregation. Christians are strangers and elect (the Greek word for church is derived from the same word) – these are two sides of a coin (1 Peter 1:1.17; 2:11).

The letter to the Hebrews develops this with particular depth. It roots Christian readers profoundly in the migrant narratives of Israel. It takes them along a path that began there but is not ended. Just as Israel once hoped (and still hopes) for the arrival and rest (Deut 12:9; Ps 95:11) that God promised (and still promises) with the Exodus from Egypt, those who believe in Christ are on an exodus journey and traveling towards the fulfillment of the promises of God for rest (Heb 4:9). As Abraham, who set out obediently “for a place that he was to receive as an inheritance” (Heb 11:8–10), the Christians “here … have no lasting city, but … are looking for the city that is to come” (Heb 13:14). That gives rise to an attitude of yearning, seeking and looking from afar (Heb 4:11 and 11:14).

The community with and on the way to God turns the believers into migrants, so to speak. Their hopes and actions, their attitudes and behavior are not fulfilled in the here and now. They are, as Paul writes “citizens of heaven” (Phil 1:27; 3:20) and therefore “not of this world”. The church, and faith, look with the eyes of “spiritual migrants”, perceiving the reality of migration and the faith of migrants as in a mirror that reflects their true identity before God.

The question to us is: where are we still strangers, and where have we long become settled? In what direction do we want to set out and what do we want to look out for?

The people that walked in darkness…

Based on conversations with surviving refugees, Francesco Piobbichi has drawn a series of pictures depicting their memories of the shipwreck. Photo: Dirk Johnen

In the late evening of 3 October 2013 a cutter ran aground off the island of Lampedusa in the Mediterranean. On board were over 500 people from Eritrea and Somalia. The islanders heard the desperate screams but in the darkness mistook them for the screeching of seagulls. The boat sank within only a few minutes. The survivors trod water for five hours. Of the 368 people who drowned that night, 108 were close up in the hold. They included an approximately 20-year-old woman from Eritrea, who had just given birth to a baby before they both died. Some of those people are buried on Lampedusa. A small shop front displays items they had with them – garments, water bottles, Bibles and Korans, photos of relatives. A few goods and chattels that found their way into our world and bear mute witness to the ghastly gap extending between those in the land of the shadow of death and us, in the countries they were yearning to reach, in their eyes the Promised Land.

“The people that walk in darkness have seen a great light; those who lived in a land of deep darkness – on them light has shined.” (Isaiah 9:1)

We are very familiar with this as an Advent reading, but how unrealistic, even cynical it sounds when we remember those who live in darkness. Martin Buber’s translation brings it out even more: The people who wander in the dark see a great light and it shines brightly over those who live in the land of the shadow of death.

How may that sound in the ears of those startled out of sleep by the heavy boots of soldiers, who search in dusty rubble for something edible for their children, who wander around in the desert? Are the promises of the Old Testament prophets more real or less real for them than for us? How do they feel on their journey, in the dark nights?

Many who set out, impelled by hardship, cling to their faith. The Bibles and Korans they bring with them witness to that. Their faith is their only hope, and at the same time, a driving force. Hope is the motor of migration. In it lies the germ of the new life, the power to leave everything behind and start anew. What a huge effort that means! How strong must the vision be, the faith that after setting out from the land of the shadow of death, God will show the way that my feet can go?

Those who come to us testify to the faith that moves mountains, and to the hope that in the power of the Holy Spirit will overcome many kinds of obstacle.

They tell us about the great light that will one day drive away all darkness. They have seen it and say to us: the light is coming!

Paul´s missionary journeys

Pictures and realities on the way

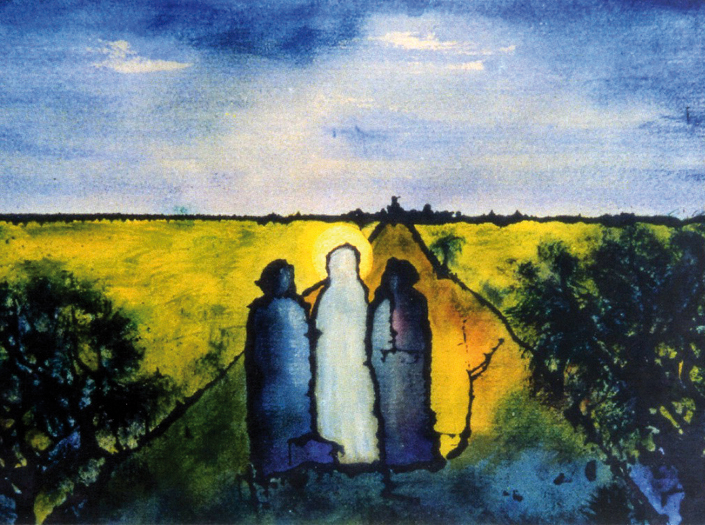

In the Bible there are many pictures on the way. The “road to Emmaus” is one of the most well known stories about walking together (Luke 24). The Unna church district, that bases its approach on the Emmaus motif, has displayed the water colour “Emmaus” painted by Iserlohn artist Ulrike Langguth for Easter 2000.

Jesus was on the move. From Nazareth to the Lake of Gennesaret, from Galilee to Jerusalem. He was an itinerant preacher. And many went with him. After his death he met two disciples on the way to Emmaus. It was only then that they grasped the deeper meaning.

In Erinnerung an das Flüchtlingsbootsunglück mit mehreren hundert Toten im Oktober 2013 vor Lampedusa setzt sich eine Adventsandacht zur Hauptvorlage mit dem biblischen Vers „Das Volk, das im Finstern wandelt …“ auseinander.

Flüchtlingen, die heute auf Lampedusa oder in Scicli ankommen, helfen die Evangelischen Kirchen in Italien mit ihrem Projekt „Mediterranean Hope“ (Hoffnung Mittelmeer)

Der Beginn des Wirkens Jesu in Galiläa

Nachdem aber Johannes überantwortet wurde, kam Jesus nach Galiläa und predigte das Evangelium Gottes. (Markus 1,14)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Jesu Stammbaum

1 Dies ist das Buch der Geschichte Jesu Christi, des Sohnes Davids, des Sohnes Abrahams. 2 Abraham zeugte Isaak. Isaak zeugte Jakob. Jakob zeugte Juda und seine Brüder. 3 Juda zeugte Perez und Serach mit der Tamar. Perez zeugte Hezron. Hezron zeugte Ram. 4 Ram zeugte Amminadab. Amminadab zeugte Nachschon. Nachschon zeugte Salmon. 5 Salmon zeugte Boas mit der Rahab. Boas zeugte Obed mit der Rut. Obed zeugte Isai. 6 Isai zeugte den König David. David zeugte Salomo mit der Frau des Uria. 7 Salomo zeugte Rehabeam. Rehabeam zeugte Abija. Abija zeugte Asa. 8 Asa zeugte Joschafat. Joschafat zeugte Joram. Joram zeugte Usija. 9 Usija zeugte Jotam. Jotam zeugte Ahas. Ahas zeugte Hiskia. 10 Hiskia zeugte Manasse. Manasse zeugte Amon. Amon zeugte Josia. 11 Josia zeugte Jojachin und seine Brüder um die Zeit der babylonischen Gefangenschaft. 12 Nach der babylonischen Gefangenschaft zeugte Jojachin Schealtiël. Schealtiël zeugte Serubbabel. 13 Serubbabel zeugte Abihud. Abihud zeugte Eljakim. Eljakim zeugte Azor. 14 Azor zeugte Zadok. Zadok zeugte Achim. Achim zeugte Eliud. 15 Eliud zeugte Eleasar. Eleasar zeugte Mattan. Mattan zeugte Jakob. 16 Jakob zeugte Josef, den Mann Marias, von der geboren ist Jesus, der da heißt Christus. 17 Alle Geschlechter von Abraham bis zu David sind vierzehn Geschlechter. Von David bis zur babylonischen Gefangenschaft sind vierzehn Geschlechter. Von der babylonischen Gefangenschaft bis zu Christus sind vierzehn Geschlechter.

Jesu Geburt

18 Die Geburt Jesu Christi geschah aber so: Als Maria, seine Mutter, dem Josef vertraut war, fand es sich, ehe sie zusammenkamen, dass sie schwanger war von dem Heiligen Geist. 19 Josef aber, ihr Mann, der fromm und gerecht war und sie nicht in Schande bringen wollte, gedachte, sie heimlich zu verlassen. 20 Als er noch so dachte, siehe, da erschien ihm ein Engel des Herrn im Traum und sprach: Josef, du Sohn Davids, fürchte dich nicht, Maria, deine Frau, zu dir zu nehmen; denn was sie empfangen hat, das ist von dem Heiligen Geist. 21 Und sie wird einen Sohn gebären, dem sollst du den Namen Jesus geben, denn er wird sein Volk retten von ihren Sünden. 22 Das ist aber alles geschehen, auf dass erfüllt würde, was der Herr durch den Propheten gesagt hat, der da spricht (Jesaja 7,14):

23 »Siehe, eine Jungfrau wird schwanger sein und einen Sohn gebären, und sie werden ihm den Namen Immanuel geben«, das heißt übersetzt: Gott mit uns.

24 Als nun Josef vom Schlaf erwachte, tat er, wie ihm der Engel des Herrn befohlen hatte, und nahm seine Frau zu sich. 25 Und er erkannte sie nicht, bis sie einen Sohn gebar; und er gab ihm den Namen Jesus. (Matthäusevangelium, Kapitel 2)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Die Aussendung der Zwölf

5 Diese Zwölf sandte Jesus aus, gebot ihnen und sprach: Geht nicht den Weg zu den Heiden und zieht nicht in eine Stadt der Samariter, 6 sondern geht hin zu den verlorenen Schafen aus dem Hause Israel. (Matthäusevangelium, Kapitel 10)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Die kanaanäische Frau

21 Und Jesus ging weg von dort und entwich in die Gegend von Tyrus und Sidon. 22 Und siehe, eine kanaanäische Frau kam aus diesem Gebiet und schrie: Ach, Herr, du Sohn Davids, erbarme dich meiner! Meine Tochter wird von einem bösen Geist übel geplagt. 23 Er aber antwortete ihr kein Wort. Da traten seine Jünger zu ihm, baten ihn und sprachen: Lass sie doch gehen, denn sie schreit uns nach. 24 Er antwortete aber und sprach: Ich bin nur gesandt zu den verlorenen Schafen des Hauses Israel. 25 Sie aber kam und fiel vor ihm nieder und sprach: Herr, hilf mir! 26 Aber er antwortete und sprach: Es ist nicht recht, dass man den Kindern ihr Brot nehme und werfe es vor die Hunde. 27 Sie sprach: Ja, Herr; aber doch essen die Hunde von den Brosamen, die vom Tisch ihrer Herren fallen. 28 Da antwortete Jesus und sprach zu ihr: Frau, dein Glaube ist groß. Dir geschehe, wie du willst! Und ihre Tochter wurde gesund zu derselben Stunde. (Matthäusevangelium, Kapitel 15)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

18 Und Jesus trat herzu, redete mit ihnen und sprach: Mir ist gegeben alle Gewalt im Himmel und auf Erden.19 Darum gehet hin und lehret alle Völker: Taufet sie auf den Namen des Vaters und des Sohnes und des Heiligen Geistes20 und lehret sie halten alles, was ich euch befohlen habe. Und siehe, ich bin bei euch alle Tage bis an der Welt Ende. (Matthäusevangelium, Kapitel 28)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Der Hauptmann Kornelius

1 Es war aber ein Mann in Cäsarea mit Namen Kornelius, ein Hauptmann der Kohorte, die die Italische genannt wurde. 2 Der war fromm und gottesfürchtig mit seinem ganzen Haus und gab dem Volk viele Almosen und betete immer zu Gott. 3 Der hatte eine Erscheinung um die neunte Stunde am Tage und sah deutlich einen Engel Gottes bei sich eintreten; der sprach zu ihm: Kornelius! 4 Er aber sah ihn an, erschrak und fragte: Herr, was ist? Der sprach zu ihm: Deine Gebete und deine Almosen sind gekommen vor Gott, dass er ihrer gedenkt. 5 Und nun sende Männer nach Joppe und lass holen Simon mit dem Beinamen Petrus. 6 Der ist zu Gast bei einem Gerber Simon, dessen Haus am Meer liegt. 7 Und als der Engel, der mit ihm redete, hinweggegangen war, rief Kornelius zwei seiner Knechte und einen frommen Soldaten von denen, die ihm dienten, 8 und erzählte ihnen alles und sandte sie nach Joppe.

9 Am nächsten Tag, als diese auf dem Wege waren und in die Nähe der Stadt kamen, stieg Petrus auf das Dach, zu beten um die sechste Stunde. 10 Und als er hungrig wurde, wollte er essen. Während sie ihm aber etwas zubereiteten, kam eine Verzückung über ihn, 11 und er sah den Himmel aufgetan und ein Gefäß herabkommen wie ein großes leinenes Tuch, an vier Zipfeln niedergelassen auf die Erde. 12 Darin waren allerlei vierfüßige und kriechende Tiere der Erde und Vögel des Himmels. 13 Und es geschah eine Stimme zu ihm: Steh auf, Petrus, schlachte und iss! 14 Petrus aber sprach: O nein, Herr; denn ich habe noch nie etwas Gemeines und Unreines gegessen. 15 Und die Stimme sprach zum zweiten Mal zu ihm: Was Gott rein gemacht hat, das nenne du nicht unrein. 16 Und das geschah dreimal; und alsbald wurde das Gefäß wieder hinaufgenommen gen Himmel.

17 Als aber Petrus noch ratlos war, was die Erscheinung bedeute, die er gesehen hatte, siehe, da fragten die Männer, von Kornelius gesandt, nach dem Haus Simons und standen schon an der Tür, 18 riefen und fragten, ob Simon mit dem Beinamen Petrus hier zu Gast wäre. 19 Während aber Petrus nachsann über die Erscheinung, sprach der Geist zu ihm: Siehe, drei Männer suchen dich; 20 so steh auf, steig hinab und geh mit ihnen und zweifle nicht, denn ich habe sie gesandt.

21 Da stieg Petrus hinab zu den Männern und sprach: Siehe, ich bin’s, den ihr sucht; aus welchem Grund seid ihr hier? 22 Sie aber sprachen: Der Hauptmann Kornelius, ein frommer und gottesfürchtiger Mann mit gutem Ruf bei dem ganzen Volk der Juden, hat einen Befehl empfangen von einem heiligen Engel, dass er dich sollte holen lassen in sein Haus und hören, was du zu sagen hast. 23 Da rief er sie herein und beherbergte sie. Am nächsten Tag machte er sich auf und zog mit ihnen, und einige Brüder aus Joppe gingen mit ihm. 24 Und am folgenden Tag kam er nach Cäsarea. Kornelius aber wartete auf sie und hatte seine Verwandten und nächsten Freunde zusammengerufen. 25 Und als Petrus hereinkam, ging ihm Kornelius entgegen und fiel ihm zu Füßen und betete ihn an. 26 Petrus aber richtete ihn auf und sprach: Steh auf, auch ich bin ein Mensch. 27 Und während er mit ihm redete, ging er hinein und fand viele, die zusammengekommen waren. 28 Und er sprach zu ihnen: Ihr wisst, dass es einem jüdischen Mann nicht erlaubt ist, mit einem Fremden umzugehen oder zu ihm zu kommen; aber Gott hat mir gezeigt, dass ich keinen Menschen gemein oder unrein nennen soll. 29 Darum habe ich mich nicht geweigert zu kommen, als ich geholt wurde. So frage ich euch nun, warum ihr mich habt holen lassen.

30 Kornelius sprach: Vor vier Tagen um diese Zeit betete ich um die neunte Stunde in meinem Hause. Und siehe, da stand ein Mann vor mir in einem leuchtenden Gewand 31 und sprach: Kornelius, dein Gebet ist erhört und deiner Almosen ist gedacht worden vor Gott. 32 So sende nun nach Joppe und lass herrufen Simon mit dem Beinamen Petrus, der zu Gast ist im Hause des Gerbers Simon am Meer. 33 Da sandte ich sofort zu dir; und du hast recht getan, dass du gekommen bist. Nun sind wir alle hier vor Gott zugegen, um alles zu hören, was dir vom Herrn befohlen ist.

34 Petrus aber tat seinen Mund auf und sprach: Nun erfahre ich in Wahrheit, dass Gott die Person nicht ansieht; 35 sondern in jedem Volk, wer ihn fürchtet und Recht tut, der ist ihm angenehm. 36 Er hat das Wort dem Volk Israel gesandt und Frieden verkündigt durch Jesus Christus, welcher ist Herr über alles. 37 Ihr wisst, was in ganz Judäa geschehen ist, angefangen von Galiläa nach der Taufe, die Johannes predigte, 38 wie Gott Jesus von Nazareth gesalbt hat mit Heiligem Geist und Kraft; der ist umhergezogen und hat Gutes getan und alle gesund gemacht, die in der Gewalt des Teufels waren, denn Gott war mit ihm. 39 Und wir sind Zeugen für alles, was er getan hat im jüdischen Land und in Jerusalem. Den haben sie an das Holz gehängt und getötet. 40 Den hat Gott auferweckt am dritten Tag und hat ihn erscheinen lassen, 41 nicht dem ganzen Volk, sondern uns, den von Gott vorher erwählten Zeugen, die wir mit ihm gegessen und getrunken haben, nachdem er auferstanden war von den Toten. 42 Und er hat uns geboten, dem Volk zu predigen und zu bezeugen, dass er von Gott bestimmt ist zum Richter der Lebenden und der Toten. 43 Von diesem bezeugen alle Propheten, dass durch seinen Namen alle, die an ihn glauben, Vergebung der Sünden empfangen sollen. 44 Da Petrus noch diese Worte redete, fiel der Heilige Geist auf alle, die dem Wort zuhörten. 45 Und die gläubig gewordenen Juden, die mit Petrus gekommen waren, entsetzten sich, weil auch auf die Heiden die Gabe des Heiligen Geistes ausgegossen wurde; 46 denn sie hörten, dass sie in Zungen redeten und Gott hoch priesen. Da antwortete Petrus: 47 Kann auch jemand denen das Wasser zur Taufe verwehren, die den Heiligen Geist empfangen haben ebenso wie wir? 48 Und er befahl, sie zu taufen in dem Namen Jesu Christi. Da baten sie ihn, dass er noch einige Tage dabliebe. (Apostelgeschichte, Kapitel 10)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

1 Saulus aber schnaubte noch mit Drohen und Morden gegen die Jünger des Herrn und ging zum Hohenpriester 2 und bat ihn um Briefe nach Damaskus an die Synagogen, dass er Anhänger dieses Weges, Männer und Frauen, wenn er sie fände, gefesselt nach Jerusalem führe. (Apostelgeschichte 9, 1+2)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Erste Christen in Antiochia

19 Die aber zerstreut waren wegen der Verfolgung, die sich wegen Stephanus erhob, gingen bis nach Phönizien und Zypern und Antiochia und verkündigten das Wort niemandem als allein den Juden. 20 Es waren aber einige unter ihnen, Männer aus Zypern und Kyrene, die kamen nach Antiochia und redeten auch zu den Griechen und predigten das Evangelium vom Herrn Jesus. (Apostelgeschichte 11, 19-20)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

In Korinth

1 Danach verließ Paulus Athen und kam nach Korinth 2 und fand einen Juden mit Namen Aquila, aus Pontus gebürtig; der war mit seiner Frau Priszilla kürzlich aus Italien gekommen, weil Kaiser Klaudius allen Juden geboten hatte, Rom zu verlassen. Zu denen ging Paulus. 3 Und weil er das gleiche Handwerk hatte, blieb er bei ihnen und arbeitete; sie waren nämlich von Beruf Zeltmacher. (Apostelgeschichte 18, 1-3)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

3 Grüßt die Priska und den Aquila, meine Mitarbeiter in Christus Jesus, 4 die für mein Leben ihren Hals hingehalten haben, denen nicht allein ich danke, sondern alle Gemeinden der Heiden, 5 und die Gemeinde in ihrem Haus. (Römer 16, 3-5)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Der Ruf nach Makedonien

9 Und Paulus sah eine Erscheinung bei Nacht: Ein Mann aus Makedonien stand da und bat ihn: Komm herüber nach Makedonien und hilf uns! 10 Als er aber die Erscheinung gesehen hatte, da suchten wir sogleich nach Makedonien zu reisen, gewiss, dass uns Gott dahin berufen hatte, ihnen das Evangelium zu predigen. In Philippi 11 Da fuhren wir von Troas ab und kamen geradewegs nach Samothrake, am nächsten Tag nach Neapolis 12 und von da nach Philippi, das ist eine Stadt des ersten Bezirks von Makedonien, eine römische Kolonie. Wir blieben aber einige Tage in dieser Stadt. 13 Am Sabbattag gingen wir hinaus vor das Stadttor an den Fluss, wo wir dachten, dass man zu beten pflegte, und wir setzten uns und redeten mit den Frauen, die dort zusammenkamen.

Die Bekehrung der Lydia

14 Und eine Frau mit Namen Lydia, eine Purpurhändlerin aus der Stadt Thyatira, eine Gottesfürchtige, hörte zu; der tat der Herr das Herz auf, sodass sie darauf achthatte, was von Paulus geredet wurde. 15 Als sie aber mit ihrem Hause getauft war, bat sie uns und sprach: Wenn ihr anerkennt, dass ich an den Herrn glaube, so kommt in mein Haus und bleibt da. Und sie nötigte uns.

Die Magd mit dem Wahrsagegeist

16 Es geschah aber, als wir zum Gebet gingen, da begegnete uns eine Magd, die hatte einen Wahrsagegeist und brachte ihren Herren viel Gewinn ein mit ihrem Wahrsagen. 17 Die folgte Paulus und uns überall hin und schrie: Diese Menschen sind Knechte des höchsten Gottes, die euch den Weg des Heils verkündigen. 18 Das tat sie viele Tage lang. Paulus war darüber so aufgebracht, dass er sich umwandte und zu dem Geist sprach: Ich gebiete dir im Namen Jesu Christi, dass du von ihr ausfährst. Und er fuhr aus zu derselben Stunde. 19 Als aber ihre Herren sahen, dass damit ihre Hoffnung auf Gewinn ausgefahren war, ergriffen sie Paulus und Silas, schleppten sie auf den Markt vor die Oberen 20 und führten sie den Stadtrichtern vor und sprachen: Diese Menschen bringen unsre Stadt in Aufruhr; sie sind Juden 21 und verkünden Sitten, die wir weder annehmen noch einhalten dürfen, weil wir Römer sind. 22 Und das Volk wandte sich gegen sie; und die Stadtrichter ließen ihnen die Kleider herunterreißen und befahlen, sie mit Stöcken zu schlagen.

Paulus und Silas im Gefängnis

23 Nachdem man sie hart geschlagen hatte, warf man sie ins Gefängnis und befahl dem Kerkermeister, sie gut zu bewachen. 24 Als er diesen Befehl empfangen hatte, warf er sie in das innerste Gefängnis und legte ihre Füße in den Block. 25 Um Mitternacht aber beteten Paulus und Silas und lobten Gott. Und es hörten sie die Gefangenen. 26 Plötzlich aber geschah ein großes Erdbeben, sodass die Grundmauern des Gefängnisses wankten. Und sogleich öffneten sich alle Türen und von allen fielen die Fesseln ab. Als aber der Kerkermeister aus dem Schlaf auffuhr und sah die Türen des Gefängnisses offen stehen, zog er das Schwert und wollte sich selbst töten; denn er meinte, die Gefangenen wären entflohen. 28 Paulus aber rief laut: Tu dir nichts an; denn wir sind alle hier! 29 Der aber forderte ein Licht und stürzte hinein und fiel zitternd Paulus und Silas zu Füßen. 30 Und er führte sie heraus und sprach: Ihr Herren, was muss ich tun, dass ich gerettet werde? 31 Sie sprachen: Glaube an den Herrn Jesus, so wirst du und dein Haus selig! 32 Und sie sagten ihm das Wort des Herrn und allen, die in seinem Hause waren. 33 Und er nahm sie zu sich in derselben Stunde der Nacht und wusch ihnen die Striemen. Und er ließ sich und alle die Seinen sogleich taufen 34 und führte sie in sein Haus und bereitete ihnen den Tisch und freute sich mit seinem ganzen Hause, dass er zum Glauben an Gott gekommen war. 35 Als es aber Tag geworden war, sandten die Stadtrichter die Gerichtsdiener und ließen sagen: Lass diese Männer frei! 36 Und der Kerkermeister überbrachte Paulus diese Botschaft: Die Stadtrichter haben hergesandt, dass ihr frei sein sollt. Nun kommt heraus und geht hin in Frieden! 37 Paulus aber sprach zu ihnen: Sie haben uns ohne Recht und Urteil öffentlich geschlagen, die wir doch römische Bürger sind, und in das Gefängnis geworfen, und sollten uns nun heimlich fortschicken? Nein! Sie sollen selbst kommen und uns hinausführen! 38 Die Gerichtsdiener berichteten diese Worte den Stadtrichtern. Da fürchteten sie sich, als sie hörten, dass sie römische Bürger wären, 39 und kamen und redeten ihnen zu, führten sie heraus und baten sie, die Stadt zu verlassen. 40 Da gingen sie aus dem Gefängnis und gingen zu der Lydia. Und als sie die Brüder und Schwestern gesehen und sie getröstet hatten, zogen sie fort.

(Apostelgeschichte 16, 9-40)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Von den Schwachen und Starken im Glauben

1 Den Schwachen im Glauben nehmt an und streitet nicht über Meinungen. 2 Der eine glaubt, er dürfe alles essen. Der Schwache aber isst kein Fleisch. 3 Wer isst, der verachte den nicht, der nicht isst; und wer nicht isst, der richte den nicht, der isst; denn Gott hat ihn angenommen. 4 Wer bist du, dass du einen fremden Knecht richtest? Er steht oder fällt seinem Herrn. Er wird aber stehen bleiben; denn der Herr kann ihn aufrecht halten. 5 Der eine hält einen Tag für höher als den andern; der andere aber hält alle Tage für gleich. Ein jeder sei seiner Meinung gewiss. 6 Wer auf den Tag achtet, der tut’s im Blick auf den Herrn; wer isst, der isst im Blick auf den Herrn, denn er dankt Gott; und wer nicht isst, der isst im Blick auf den Herrn nicht und dankt Gott auch. 7 Denn unser keiner lebt sich selber, und keiner stirbt sich selber. 8 Leben wir, so leben wir dem Herrn; sterben wir, so sterben wir dem Herrn. Darum: wir leben oder sterben, so sind wir des Herrn. 9 Denn dazu ist Christus gestorben und wieder lebendig geworden, dass er über Tote und Lebende Herr sei. 10 Du aber, was richtest du deinen Bruder? Oder du, was verachtest du deinen Bruder? Wir werden alle vor den Richterstuhl Gottes gestellt werden. 11 Denn es steht geschrieben (Jesaja 45,23): »So wahr ich lebe, spricht der Herr, mir sollen sich alle Knie beugen, und alle Zungen sollen Gott bekennen.« 12 So wird nun jeder von uns für sich selbst Gott Rechenschaft geben. 13 Darum lasst uns nicht mehr einer den andern richten; sondern richtet vielmehr darauf euren Sinn, dass niemand seinem Bruder einen Anstoß oder Ärgernis bereite. 14 Ich weiß und bin gewiss in dem Herrn Jesus, dass nichts unrein ist an sich selbst; nur für den, der es für unrein hält, für den ist es unrein. 15 Wenn aber dein Bruder wegen deiner Speise betrübt wird, so handelst du nicht mehr nach der Liebe. Bringe nicht durch deine Speise den ins Verderben, für den Christus gestorben ist. 16 Es soll doch nicht verlästert werden, was ihr Gutes habt. 17 Denn das Reich Gottes ist nicht Essen und Trinken, sondern Gerechtigkeit und Friede und Freude im Heiligen Geist. 18 Wer darin Christus dient, der ist Gott wohlgefällig und bei den Menschen geachtet. 19 Darum lasst uns dem nachstreben, was zum Frieden dient und zur Erbauung untereinander. 20 Zerstöre nicht um der Speise willen Gottes Werk. Es ist zwar alles rein; aber es ist nicht gut für den, der es isst mit schlechtem Gewissen. 21 Es ist besser, du isst kein Fleisch und trinkst keinen Wein und tust nichts, woran dein Bruder Anstoß nimmt. 22 Den Glauben, den du hast, habe für dich selbst vor Gott. Selig ist, der sich selbst nicht verurteilen muss in dem, was er gut heißt. 23 Wer aber zweifelt und dennoch isst, der ist schon verurteilt, denn es kommt nicht aus dem Glauben. Was aber nicht aus dem Glauben kommt, das ist Sünde.

(Römer 14)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

11 Als aber Kephas nach Antiochia kam, widerstand ich ihm ins Angesicht, denn er hatte sich ins Unrecht gesetzt. 12 Denn bevor einige von Jakobus kamen, aß er mit den Heiden; als sie aber kamen, zog er sich zurück und sonderte sich ab, weil er die aus der Beschneidung fürchtete. 13 Und mit ihm heuchelten auch die andern Juden, sodass selbst Barnabas verführt wurde, mit ihnen zu heucheln. 14 Als ich aber sah, dass sie nicht richtig handelten nach der Wahrheit des Evangeliums, sprach ich zu Kephas öffentlich vor allen: Wenn du, der du ein Jude bist, heidnisch lebst und nicht jüdisch, warum zwingst du dann die Heiden, jüdisch zu leben?

(Galater 2,11-14)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Freiheit in Christus

1 Zur Freiheit hat uns Christus befreit! So steht nun fest und lasst euch nicht wieder das Joch der Knechtschaft auflegen! 2 Siehe, ich, Paulus, sage euch: Wenn ihr euch beschneiden lasst, so wird euch Christus nichts nützen. 3 Ich bezeuge abermals einem jeden, der sich beschneiden lässt, dass er das ganze Gesetz zu tun schuldig ist. 4 Ihr habt Christus verloren, die ihr durch das Gesetz gerecht werden wollt, aus der Gnade seid ihr herausgefallen. 5 Denn wir warten im Geist durch den Glauben auf die Gerechtigkeit, auf die wir hoffen. 6 Denn in Christus Jesus gilt weder Beschneidung noch Unbeschnittensein etwas, sondern der Glaube, der durch die Liebe tätig ist.

(Galater 5,1-6)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Vom Essen des Götzenopferfleisches

1 Was aber das Götzenopfer angeht, so wissen wir, dass wir alle die Erkenntnis haben. Die Erkenntnis bläht auf; aber die Liebe baut auf. 2 Wenn jemand meint, er habe etwas erkannt, der hat noch nicht erkannt, wie man erkennen soll. 3 Wenn aber jemand Gott liebt, der ist von ihm erkannt. 4 Was nun das Essen von Götzenopferfleisch angeht, so wissen wir, dass es keinen Götzen gibt in der Welt und keinen Gott als den einen. 5 Und obwohl es solche gibt, die Götter genannt werden, es sei im Himmel oder auf Erden, wie es ja viele Götter und viele Herren gibt, 6 so haben wir doch nur einen Gott, den Vater, von dem alle Dinge sind und wir zu ihm, und einen Herrn, Jesus Christus, durch den alle Dinge sind und wir durch ihn. 7 Aber nicht alle haben die Erkenntnis. Einige essen’s als Götzenopfer, weil sie immer noch an die Götzen gewöhnt sind; und so wird ihr Gewissen, weil es schwach ist, befleckt. 8 Aber die Speise macht’s nicht, wie wir vor Gott stehen. Essen wir nicht, so fehlt uns nichts, essen wir, so gewinnen wir nichts. 9 Seht aber zu, dass diese eure Freiheit für die Schwachen nicht zum Anstoß wird! 10 Denn wenn jemand dich, der du die Erkenntnis hast, im Götzentempel zu Tisch sitzen sieht, wird dann nicht sein Gewissen, da er doch schwach ist, verleitet, das Götzenopfer zu essen? Und so geht durch deine Erkenntnis der Schwache zugrunde, der Bruder, für den doch Christus gestorben ist. 12 Wenn ihr aber so sündigt an den Brüdern und Schwestern und verletzt ihr schwaches Gewissen, so sündigt ihr an Christus. 13 Darum, wenn Speise meinen Bruder zu Fall bringt, will ich nimmermehr Fleisch essen, auf dass ich meinen Bruder nicht zu Fall bringe.

(1. Korinther 8)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Die Apostelversammlung in Jerusalem

Und einige kamen herab von Judäa und lehrten die Brüder: Wenn ihr euch nicht beschneiden lasst nach der Ordnung des Mose, könnt ihr nicht selig werden. 2 Da nun Zwietracht entstand und Paulus und Barnabas einen nicht geringen Streit mit ihnen hatten, ordnete man an, dass Paulus und Barnabas und einige andre von ihnen nach Jerusalem hinaufziehen sollten zu den Aposteln und Ältesten um dieser Frage willen. 3 Und sie wurden von der Gemeinde geleitet und zogen durch Phönizien und Samarien und erzählten von der Bekehrung der Heiden und machten damit allen Brüdern und Schwestern große Freude.

4 Als sie aber nach Jerusalem kamen, wurden sie empfangen von der Gemeinde und von den Aposteln und von den Ältesten. Und sie verkündeten, wie viel Gott mit ihnen getan hatte. 5 Da traten einige von der Gruppe der Pharisäer auf, die gläubig geworden waren, und sprachen: Man muss sie beschneiden und ihnen gebieten, das Gesetz des Mose zu halten. 6 Da kamen die Apostel und die Ältesten zusammen, über diese Sache zu beraten.

7 Als man sich aber lange gestritten hatte, stand Petrus auf und sprach zu ihnen: Ihr Männer, liebe Brüder, ihr wisst, dass Gott vor langer Zeit unter euch bestimmt hat, dass durch meinen Mund die Heiden das Wort des Evangeliums hören und glauben. 8 Und Gott, der die Herzen kennt, hat es bezeugt und ihnen den Heiligen Geist gegeben wie auch uns, 9 und er hat keinen Unterschied gemacht zwischen uns und ihnen und reinigte ihre Herzen durch den Glauben. 10 Warum versucht ihr denn nun Gott dadurch, dass ihr ein Joch auf den Nacken der Jünger legt, das weder unsre Väter noch wir haben tragen können? 11 Vielmehr glauben wir, durch die Gnade des Herrn Jesus selig zu werden, auf gleiche Weise wie auch sie. 12 Da schwieg die ganze Menge still und hörte Paulus und Barnabas zu, die erzählten, wie große Zeichen und Wunder Gott durch sie getan hatte unter den Heiden.

13 Danach, als sie schwiegen, antwortete Jakobus und sprach: Ihr Männer, liebe Brüder, hört mir zu! 14 Simon hat erzählt, wie zuerst Gott darauf geschaut hat, aus den Heiden ein Volk für seinen Namen zu gewinnen. 15 Und damit stimmen die Worte der Propheten überein, wie geschrieben steht (Amos 9,11-12): 16 »Danach will ich mich wieder zu ihnen wenden und will die zerfallene Hütte Davids wieder bauen, und ihre Trümmer will ich wieder aufbauen und will sie aufrichten, 17 auf dass die, die von den Menschen übrig geblieben sind, nach dem Herrn fragen, dazu alle Heiden, über die mein Name genannt ist, spricht der Herr, der tut, 18 was von Anbeginn bekannt ist.« 19 Darum meine ich, dass man die von den Heiden, die sich zu Gott bekehren, nicht beschweren soll, 20 sondern ihnen schreibe, dass sie sich enthalten sollen von Befleckung durch Götzen und von Unzucht und vom Erstickten und vom Blut. 21 Denn Mose hat von alten Zeiten her in allen Städten solche, die ihn predigen, und wird an jedem Sabbat in den Synagogen gelesen.

Die Beschlüsse der Apostelversammlung

22 Da beschlossen die Apostel und Ältesten mit der ganzen Gemeinde, aus ihrer Mitte Männer auszuwählen und mit Paulus und Barnabas nach Antiochia zu senden, nämlich Judas mit dem Beinamen Barsabbas und Silas, angesehene Männer unter den Brüdern. 23 Und sie gaben ein Schreiben in ihre Hand, also lautend: Wir, die Apostel und Ältesten, eure Brüder, grüßen die Brüder aus den Heiden in Antiochia und Syrien und Kilikien. 24 Weil wir gehört haben, dass einige von den Unsern, denen wir doch nichts befohlen hatten, euch mit Lehren irregemacht und eure Seelen verwirrt haben, 25 so haben wir, einmütig versammelt, beschlossen, Männer auszuwählen und zu euch zu senden mit unsern geliebten Brüdern Barnabas und Paulus, 26 Menschen, die ihr Leben eingesetzt haben für den Namen unseres Herrn Jesus Christus. 27 So haben wir Judas und Silas gesandt, die euch mündlich dasselbe mitteilen werden. 28 Denn es gefällt dem Heiligen Geist und uns, euch weiter keine Last aufzuerlegen als nur diese notwendigen Dinge: 29 dass ihr euch enthaltet vom Götzenopferfleisch und vom Blut und vom Erstickten und von Unzucht. Wenn ihr euch davor bewahrt, tut ihr recht. Lebt wohl!

Die Benachrichtigung der Gemeinde in Antiochia

30 Als man sie hatte ziehen lassen, kamen sie nach Antiochia und versammelten die Gemeinde und übergaben den Brief. 31 Als sie ihn lasen, wurden sie über den Zuspruch froh. 32 Judas aber und Silas, die selbst Propheten waren, ermahnten die Brüder und Schwestern mit vielen Reden und stärkten sie. 33-34 Und als sie eine Zeit lang dort verweilt hatten, ließen die Brüder sie mit Frieden ziehen zu denen, die sie gesandt hatten. 35 Paulus und Barnabas aber blieben in Antiochia, lehrten und predigten mit vielen andern das Wort des Herrn.

Der Beginn der zweiten Missionsreise

36 Nach einigen Tagen sprach Paulus zu Barnabas: Lass uns wieder aufbrechen und nach unsern Brüdern und Schwestern sehen in allen Städten, in denen wir das Wort des Herrn verkündigt haben, wie es um sie steht. 37 Barnabas aber wollte, dass sie auch Johannes mit dem Beinamen Markus mitnähmen. 38 Paulus aber hielt es nicht für richtig, jemanden mitzunehmen, der sie in Pamphylien verlassen hatte und nicht mit ihnen ans Werk gegangen war. 39 Und sie kamen scharf aneinander, sodass sie sich trennten. Barnabas nahm Markus mit sich und fuhr nach Zypern. 40 Paulus aber wählte Silas und zog fort, von den Brüdern der Gnade Gottes befohlen. 41 Er zog aber durch Syrien und Kilikien und stärkte die Gemeinden.

(Apostelgeschichte 15)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

28 Hier ist nicht Jude noch Grieche, hier ist nicht Sklave noch Freier, hier ist nicht Mann noch Frau; denn ihr seid allesamt einer in Christus Jesus.

(Galater 3,28)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Die Einheit der Gemeinde aus Juden und Heiden

11 Darum denkt daran, dass ihr, die ihr einst nach dem Fleisch Heiden wart und »Unbeschnittenheit« genannt wurdet von denen, die genannt sind »Beschneidung«, die am Fleisch mit der Hand geschieht, 12 dass ihr zu jener Zeit ohne Christus wart, ausgeschlossen vom Bürgerrecht Israels und den Bundesschlüssen der Verheißung fremd; daher hattet ihr keine Hoffnung und wart ohne Gott in der Welt. 13 Jetzt aber in Christus Jesus seid ihr, die ihr einst fern wart, nahe geworden durch das Blut Christi. 14 Denn er ist unser Friede, der aus beiden eins gemacht hat und hat den Zaun abgebrochen, der dazwischen war, indem er durch sein Fleisch die Feindschaft wegnahm. 15 Er hat das Gesetz, das in Gebote gefasst war, abgetan, damit er in sich selber aus den zweien einen neuen Menschen schaffe und Frieden mache 16 und die beiden versöhne mit Gott in einem Leib durch das Kreuz, indem er die Feindschaft tötete durch sich selbst. 17 Und er ist gekommen und hat im Evangelium Frieden verkündigt euch, die ihr fern wart, und Frieden denen, die nahe waren. 18 Denn durch ihn haben wir alle beide in einem Geist den Zugang zum Vater. 19 So seid ihr nun nicht mehr Gäste und Fremdlinge, sondern Mitbürger der Heiligen und Gottes Hausgenossen, 20 erbaut auf den Grund der Apostel und Propheten, da Jesus Christus der Eckstein ist, 21 auf welchem der ganze Bau ineinandergefügt wächst zu einem heiligen Tempel in dem Herrn. 22 Durch ihn werdet auch ihr mit erbaut zu einer Wohnung Gottes im Geist.

(Epheser 2, 11-22)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

35 I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in.

38 When did we see you a stranger and invite you in, or needing clothes and clothe you?

43 I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.

(Matthäus 25, 35.38.43)

www.bibleserver.com, New International Version

Wer dem Geringen Gewalt tut, lästert dessen Schöpfer; aber wer sich des Armen erbarmt, der ehrt Gott.

(Sprüche 14,31)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

26 Und Gott sprach: Lasset uns Menschen machen, ein Bild, das uns gleich sei, die da herrschen über die Fische im Meer und über die Vögel unter dem Himmel und über das Vieh und über die ganze Erde und über alles Gewürm, das auf Erden kriecht.

(1. Mose 1,26)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Chapter 1

1 Peter, an apostle of Jesus Christ, To God’s elect, exiles scattered throughout the provinces of Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia and Bithynia, 2 who have been chosen according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, through the sanctifying work of the Spirit, to be obedient to Jesus Christ and sprinkled with his blood: Grace and peace be yours in abundance.

17 Since you call on a Father who judges each person’s work impartially, live out your time as foreigners here in reverent fear.

Chapter 2

11 Dear friends, I urge you, as foreigners and exiles, to abstain from sinful desires, which wage war against your soul, 12 Live such good lives among the pagans that, though they accuse you of doing wrong, they may see your good deeds and glorify God on the day he visits us.

(1. Petrus 1, 1-2.17 und 2,11-12)

www.bibleserver.com, New International Version

9 Denn ihr seid bisher noch nicht zur Ruhe und zu dem Erbteil gekommen, das dir der Herr, dein Gott, geben wird.

(5. Mose 12,9)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

10 Vierzig Jahre war dies Volk mir zuwider, dass ich sprach: / Es sind Leute, deren Herz immer den Irrweg will und die meine Wege nicht lernen wollen, 11 sodass ich schwor in meinem Zorn: Sie sollen nicht zu meiner Ruhe kommen.«

(Psalm 95, 10+11)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

9 Es ist also noch eine Ruhe vorhanden für das Volk Gottes.

(Hebräer 4,9)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

8 Durch den Glauben wurde Abraham gehorsam, als er berufen wurde, an einen Ort zu ziehen, den er erben sollte; und er zog aus und wusste nicht, wo er hinkäme. 9 Durch den Glauben ist er ein Fremdling gewesen im Land der Verheißung wie in einem fremden Land und wohnte in Zelten mit Isaak und Jakob, den Miterben derselben Verheißung. 10 Denn er wartete auf die Stadt, die einen festen Grund hat, deren Baumeister und Schöpfer Gott ist.

(Hebräer 11,8-10)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

14 Denn wir haben hier keine bleibende Stadt, sondern die zukünftige suchen wir.

(Hebräer 13,14)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

11 So lasst uns nun bemüht sein, in diese Ruhe einzugehen, damit nicht jemand zu Fall komme wie in diesem Beispiel des Ungehorsams.

(Hebräer 4,11)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

14 Wenn sie aber solches sagen, geben sie zu verstehen, dass sie ein Vaterland suchen.

(Hebräer 11,14)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

27 Wandelt nur würdig des Evangeliums Christi, damit ich – ob ich komme und euch sehe oder abwesend bin – von euch erfahre, dass ihr in einem Geist steht und einmütig mit uns kämpft für den Glauben des Evangeliums.

(Philipper 1,27)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

20 Wir aber sind Bürger im Himmel; woher wir auch erwarten den Heiland, den Herrn Jesus Christus, 21 der unsern geringen Leib verwandeln wird, dass er gleich werde seinem verherrlichten Leibe nach der Kraft, mit der er sich alle Dinge untertan machen kann.

(Philipper 3,20+21)

Aus: Lutherbibel, revidiert 2017, © 2016 Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, Stuttgart

Translated from German

Comparing migration of our days with stories of the Bible appears a little bit naïve to me. “Stories tell of coping and flourishing of migration…the biblical texts speak of persons who do not just suffer their migration as fate but shape and change it, rendering it fruitful, knowing that they are led, sustained and gifted by God in so doing”. How should someone who sticks in a camp in Libya or lives in the streets somewhere in Italy render this migration fruitful?

That is already difficult enough here in Germany when the resident status doesn’t permit any continuing education and or job. What we consider as faith base may seem as mockery to uprooted people.

Author: Beate Ullrich

Translated from German

That is typical of our too intellectual church. The heading of the chapter:” Biblical and theological reassurance” is a linguistic monstrosity, that can hardly be understood by non-theologians. Why could the heading not be “Examples from the Bible”?

Also the term: “The Bible, a book of wandering” is misleading. The Old Testament does not speak about wandering but about land grabbing (i.a. stories of forefathers) about land defense (i.a. stories of kings), about expulsion (i.a. Babylonian captivity).

Of course it is about God’s people and the aspect of protection by the God of Israel – but it is really impossible to call this wandering (wandering is the miller’s delight).

It is urgently necessary to think about the words that are used in ecclesiastical texts. That is especially important concerning the subject of migration and flight – as it is about personal fate of people.

Author: Hansjörg Mandler

It is really sad to know that there are more 60 millions people moving around or migrating to other parts of the world due to various reasons. It is a reality faced by Churches everywhere, in Asia or Europe, for example. I can share the experiences of many women in Indonesia who have to go to overseas as domestic workers. There are more than 7 millions Indonesian migrant workers in overseas. They have to abandon their children, husbands, and parents for sake of their income. As a matter of fact, many of them face brutal experiences such as no salary, torture, rape, human trafficking, and even death. Here I would like to highlight the need of the Churches in Singapore, Malaysia, Korea, Taiwan, Hongkong, and Middle East, to encourage their respective members to practice hospitality to strangers, the migrant workers. Apart from that, the Churches in those countries need to keep speaking out to the public: please welcome the migrant workers hospitably.

Translated from German

The histories of migration in the Bible also show what people are afraid of in our days. From a minority in Egypt with a co-liability (Joseph, who later on makes his starving brothers join him) a great people emerges with own religion and culture which is not integrated. It remains strange, comes into conflict with the rulers and migrates to the Holy Land. After a long period of peregrination they settle there but not without conflicts with the locals.

Forms of fanaticism occur, that means everything of the conquered (“handed over to the spell”, that means to kill also women, children and animals). Also Esther stands for a bloody conflict between expatriated and locals. Therefor not everything should be blurred. Otherwise we don’t take the justified fears seriously which were entered into discussion in a populistic but successful way by a (former?) social democrat Thilo Sarrazin in the bestseller “Deutschland schafft sich ab” (Germany abolishes itself).

Author: Oliver Vogelsmeier